Do You Use the Word Viking Correctly?

Do you use the word Viking correctly? Language matters, and how a person uses language significantly affects their worldview and how they perceive people, objects, and concepts.

Language matters, and how a person uses language significantly affects their worldview and perception of people, objects, and concepts. It is no surprise that a growing number of people are dismayed by today’s liberal use of the word Viking to describe a significant number of things that the word initially did not. Historians have fought pitched battles over the word's origins, and many an unsuspecting Viking history fan has been on the receiving end of the ire of the word's purists. Do you use the word Viking correctly? Here, I will attempt to clarify the word's origins, its various uses across the ages, and the evolution of its modern incarnation, specifically in non-Scandinavian languages.

The Origins of the Word Viking

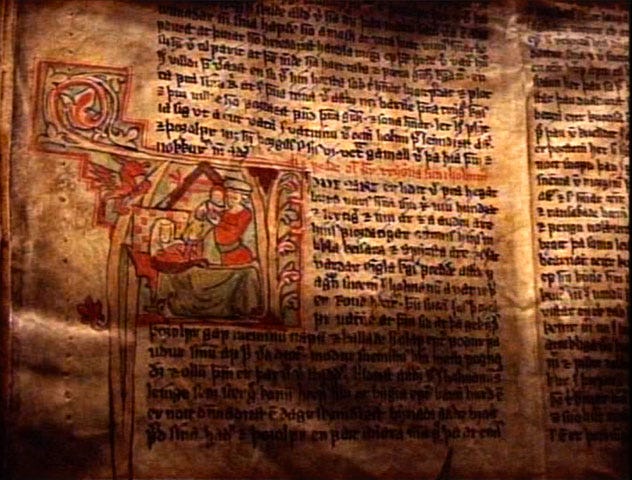

We know this for sure: the modern word Viking is derived from Old Norse via the Icelandic Sagas. Its exact origins, however, are hotly debated. Some propose the word stems from the Norse word vik, or inlet (such as those found in Fjords). Others suggest the word leaped into Old Norse from the Anglo-Saxon language that had borrowed the Frisian word Wicingas, which meant pirate. While its origins are not well understood, and historians are divided over where precisely the word originated, we know that by the time the word was made into Old Norse, it was used not only as a noun but also as a verb. The Saga of Egill Skallagrimsson, one of the most famous of the Icelandic Sagas, offers us two compelling examples of the word’s original use (keeping in mind that the Icelandic Sagas were written centuries after the Viking Age). In the opening passage, the story describes a man named Ulfr who, “lá hann í víkingu og herjaði,” which translates (roughly) to, “he was roving and fought.” In the context of the passage, the word víkingu, or Viking, describes an activity - roving - rather than the man.

Later in the saga, the word is used in a completely different way:

“With bloody brand on-striding Me bird of bane hath followed: My hurtling spear hath sounded In the swift Vikings’ charge. Raged wrathfully our battle, Ran fire o’er foemen’s rooftrees; Sound sleepeth many a warrior Slain in the city gate.”

Here, the saga's author uses the word as a noun to describe a group of people carrying out a specific action, which tells us the word may have also been used to describe the men whose profession was to rove and fight. Jugglers juggle. Traders trade. Vikings Viking.

Egill's Saga may well be the last time the word was used in the medieval period. As the Viking Age came to a close, the profession of roving and fighting declined, along with the use of the word Viking. Although modern Icelandic is the closest relative to Old Norse, Old Norse is considered a dead language. It evolved over the medieval period into the separate languages of Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, and Icelandic, and the word Viking did not make it into any of their lexicons. It disappeared almost entirely for many centuries until it experienced a revival led by 19th-century historians from Western Europe.

The Revival of the Word Viking

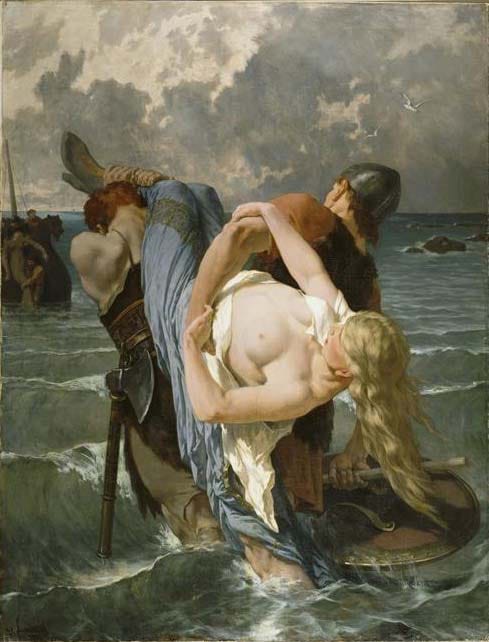

The Romantic movement of the early 19th Century (1800–1850) developed an intrinsic fascination with the medieval period. Part of that movement saw a rapid-growing interest in a little-known, poorly understood element of early medieval history: the Viking Age. Historians flocked to the field with keen interest, seeking to shed light on this “dark” age. 19th Century English historians demarcated the Viking Age between 793 A.D., the attack on Lindisfarne, and 1066 A.D., the Norman invasion of England. Both events took place in the British Isles, setting the stage for an Anglo-centric approach to studying the Vikings that persists today. They were the first to examine the sagas, search for writings about the Viking invasions of Europe, and begin to form a coherent narrative of the Viking Age. Through their efforts, Western Civilization rediscovered the long-lost history of an enigmatic people who had plagued the early kingdoms of Britain and France, among others, and whose origins they traced to Scandinavia.

During the romantic period, no one had yet discovered a longship, and no one had undertaken any archeological digs of any significance. Hence, historians had to turn to the primary sources. Those sources, tracked down across Europe, many of them hidden away in age-old university archives, cathedral libraries, and private collections owned by Europe’s ruling class, constituted close to the entire body of evidence for the Viking Age. Misconceptions about the Vikings abound in this early period of research, many of which persist today. At the same time, a new political force took hold in Western Europe, one that would co-opt the study of history for its self-serving purposes and one that ultimately would be responsible for the deaths of hundreds of millions of people in the following century: the concept of nationalism.

Beginning in the mid-19th century, the governments of Europe, both nascent democracies and established autocracies, sought to bend the narrative of history to suit their political aims and confirm their legitimacy. France, for example, developed the official national narrative that modern France emerged from the Carolingian Empire. This self-described holy Christian institution sought to stabilize Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. England developed a historical narrative revolving around the Anglo-Saxon kings, such as Alfred the Great, to emphasize that the English monarchy had had a long and rich history wherein they had fought back innumerable invasions with the help of divine intervention. Within the context of nascent national fervor, the study of the Vikings took shape. Not surprisingly, historians painted the Vikings as an outside enemy that threatened civilization and had to be defeated. The triumph of Christendom over “the ravages of heathen men,” as written in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was regarded as a pivotal, divinely ordained achievement, exploited by the governments of Europe as a means to prove the providence of their nations further and to encourage national pride.

However, the fearsome enemy of Christendom did not yet have a name. What, then, to call these invaders who attempted to thwart the Christian kingdoms of Europe? Historian Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough explains in her book Beyond the Northlands that the first modern use of the word Viking in English was recorded in 1807. The word wasn’t reserved for the “men who roved” but referred to the entire Norse world. It is, woefully, a product of the “us against them” mentality and an unfortunate oversimplification and mischaracterization of a time and people we now know to have been far more complicated than previously acknowledged. From 1807 forward, the generalized use of the word dominated the histories and the arts of the 19th and 20th centuries and is, by and large, how most people use the word today.

So, Do You Use the Word Viking Correctly?

Using the word Viking correctly boils down to effective communication. Who is the audience? What is their level of knowledge concerning the Viking Age? Making clear one's intent for the word is critical, and nowhere is this done better than in a recent book titled The Age of the Vikings by historian Anders Winroth, in which he takes the time to make clear how he intends to use the word:

“The word ‘Viking’ is rare in the Viking Age sources, but in modern times it has become a ubiquitous but ill-defined label. The term's original sense is unclear, and there are many suggestions for etymological derivations. In this book, I reserve the term ‘Vikings’ for those northerners who, in the early Middle Ages, raided, plundered and battled in Europe, in accordance with how the word is used in Medieval texts. Otherwise, I refer to the inhabitants of Scandinavia as Scandinavians. The language they spoke is called Old Norse, so I have sometimes used the term ‘Norsemen.’”

Anyone who uses the word should define how they intend to use it, and to make clear the differences between its various usages. I, for example, use the word “Viking” more interchangeably because my intended audience is those who are beginning to explore their interest in the Viking Age and who may not yet understand how its modern use differs from the past. However, in writing more in-depth histories, I focus my use of the word on the "men who roved."

Enjoy what you just read? Consider supporting my work by subscribing below.