How Salt May Have Motivated the Vikings’ Westward Raids

C.J. does a deep dive into a potentially compelling contributing factor in Viking raids

As a former school teacher, I feel compelled to first provide the following disclaimer for this article: This is not an academic paper; it’s a Substack post. While the material will feel academic (because I do publish academic papers) and is inspired by academic research, this article is meant for public consumption and entertainment. If you are a high school or college student looking to cite some of the material in this article, please get in touch with me first so I can help you with the material and citations you are looking to use. Those of you looking to dive deeper into this topic will find the bulk of my citations for my research in my selected bibliography.

From economic causes to social and political ones, historians and archeologists worldwide have put a great deal of energy into exploring the question of what may have caused the so-called Viking Age. One theory centers on the idea that the Vikings had to leave in search of specific resources, such as enslaved people, wine, and salt, to remain competitive in a shifting economic landscape at home. No one argues that acquiring portable wealth–defined as easily transportable goods of value–was the end goal of those who left Scandinavia to rove in the early Viking Age. What is less clear is what kinds of portable wealth they valued the most and how much certain kinds of portable wealth might have motivated them to take the risk of sailing to faraway places to acquire them.

The Salt Hypothesis proposes that the Vikings’ early westward expansion–defined as the first thirty or so years of Viking activity in Western France and the British Isles–was in part driven by one particular form of wealth that motivated them to travel farther and take greater risks than the others. As the title suggests, that form of portable wealth was salt. Unlike silver, enslaved people, and wine, which the Vikings could acquire closer to home, high-quality salt had to be acquired in southwestern France since the inland salt mines at Salzburg were unattainable due to the Carolingian embargo on trade with Scandinavia.

In the following article, I will lay out the case for salt as a motivating factor for some of the earliest Viking raids. I will start by establishing the Viking Age Scandinavian need for, and lack of access to, salt. I will then explore the not-so-coincidental correlation between the Vikings’ earliest raids and the monastic trade networks present in France and the British Isles. Finally, I will discuss new research on establishing the herring trade in the Baltic states that has breathed new life into the Salt Hypothesis and bring all the research into a cohesive narrative of salt’s potential role in the early phases of the so-called Viking Age.

I want to make clear at the outset that in no way am I proposing salt may have served as anything resembling a trigger event for the start of the so-called Viking Age. Attempts to define a single catalyst or trigger event have all proved unfruitful. A 2008 paper by the archeologist James Barrett called such attempts “unrealistic” and proposed the start of the Viking Age could only be defined by combining numerous factors into a broader, more general theory. I completely agree with that viewpoint. The Salt Hypothesis does not claim that the exploitation of salt in France was anything close to a catalyst but rather a phenomenon that emerged within the context of other longue-durée causes.

Initially, I set out to answer three questions: why did the Vikings attack the monastery of St. Philibert on the island of Noirmoutier, off the coast of France; why so early (they sacked it in 799 A.D.); and why so frequently (they supposedly returned every year for 30 years)? This article will focus on a localized portion of the Viking Age but also make some broader connections that, ultimately, still need to be fleshed out.

History of The Salt Hypothesis

Around 1946, the salt producers of the island of Noirmoutier in France went bankrupt. Soon, the entire industry collapsed. Today, that same salt production has seen a revival of sorts by local artisans looking to make a quick profit off tourists, but the commercial exports of the past have ceased to exist. Why did the salt industry in one of the most lucrative salt-producing parts of the world collapse in the middle of the twentieth century? Because Scandinavia, their primary market, developed refrigeration.

The sudden evaporation of the salt industry in the Southern Brittany region of France ushered in the end to two millennia of violent, bloody history over a resource that, until seventy-five years ago, was considered one of the most precious commodities in the world. Since Roman times, the island of Noirmoutier, though remote and hard to access, interested the various emperors, kings, clerics, and chieftains who controlled the region not for who lived there but for what they could make there. One such party was the Vikings.

The idea that salt may have attracted the Vikings to the region is well known. French historians have searched for decades for evidence to show that salt played a vital role in the Viking invasions of Western France and Brittany. Unfortunately, the dearth of archeological and textual evidence for a direct link between the salt trade and the Vikings has left them wanting. Although plenty of circumstantial evidence does exist, the absence of anything substantive has relegated the entire topic to the reliquary of Viking Age curiosities.

“10th century Vikings may have been attracted to the area [Noirmoutier] by the salt.”

The Salt Hypothesis has its roots in a yet unsolved mystery. In 799 A.D., according to the monk Alcuin, the islands of Aquitaine—which includes the island of Noirmoutier—were attacked by pagans. Historians have debated ad infinitum whether these so-called pagans were Vikings or if they might have been Saracens from Spain. The modern consensus is that the pagans were Vikings, further reinforced by testimony from the monk Ermentaire, who chronicled the attacks in a later text. Thus started what the Breton historian Jean-Christophe Cassard called the Century of the Vikings in Brittany. For the next thirty years, the Vikings repeatedly raided the island of Noirmoutier for its monastery, Saint Philibert.

A letter written in 819 A.D. by Abbott Arnulf of Saint Philibert complained of “frequent and persistent raids.” They occurred so frequently that the monks who resided there fled to a satellite priory on the continent every spring and summer before returning in winter. Nowhere else in Christendom did the Vikings return at such regular intervals, which has begged the question: Why? What did they find so alluring about the island? Especially after the monks started to abandon it in spring, taking their portable wealth with them?

The most current and accepted theory is that Vikings were interested in the whole region, and the monastery of Saint Philibert was a convenient place to raid. Later, when the Vikings established a foothold on the outskirts of the city of Nantes in 853 A.D. — a camp on the river island of Betia on the Loire — that may have been true. However, in the first thirty years of raiding, leading up to the definite abandonment of the island by the monks of Saint Philibert in 836 A.D., the Vikings had made little effort to raid inland. Hence, I argue, the monastery of Saint Philibert was likely a—if not the—target.

The Salt Hypothesis proposes that the Vikings returned to the island in spring and summer to raid for salt. They timed their raids to arrive in the peak salt-producing months to export it back to Scandinavia. The Salt Hypothesis further proposes that the Vikings’ need for salt significantly contributed to their westward expansion to France. Salt, the theory argues, was one of the significant contributing factors that motivated Vikings to raid the coast of France as early and as frequently as they did.

Trouble Brewing in the East

While Anglo-centric historians have defined the Viking Age as having started roughly in 793 A.D. with an event in England, recent scholarship has accepted that the Viking Age started much sooner in the East. A treasure trove of silver coins from the Muslim world found at Lake Ladoga gives us some idea of when contacts may have begun. As a standard practice in the Muslim world, coin makers imprinted minting dates on their coins, and the coins at Lake Ladoga date to the 780s.

Primary sources for the early societal structure, culture, and activities of the Swedish Vikings, known as the Rus, are practically non-existent. They did not leave us any written sources besides disparate runes carved into wood planks or stones. One mention in the Annals of St. Bertin tells us of a diplomatic delegation from Constantinople that visited Louis I in Aachen in 839 A.D. that included Rus. Still, we have no other historical sources predating that mention. Thus, we must turn to archeological evidence.

Combined with further archeological evidence of pre-Viking Age colonies on the eastern shores of the Baltic, such as the Grobin colony in what is now Latvia, trade contacts between Sweden and the Middle East appear to have begun several decades before the Danes and Norwegians launched their first raids against the British Isles and France. Those early contacts appear not to have been violent, either. The earliest graves from the Grobin colony (pre-800s) include women and children, signaling a peaceful colonization effort, whereas later graves (mid-800s and later) contain fighting-aged men and their weapons.

Why the eastward expansion transitioned from trading to raiding remains a complex question with no precise answer. However, they may have been victims of their own success. Of all the longue-durée causes that contributed to the genesis of the eastward expansion and, by extension, the westward expansion, Søren Sindbæk’s synthesis on the role of the silver economy, urbanism, and the movement of durable goods as primary drivers perhaps has the best grasp on solving the mystery. Sindbæk and other historians have stressed at length the importance of the social bonds of the nuclear family, as well as the value of establishing familial ties, leading to a silver economy attached to the cultural practice of the bride-price. As Sindbæk wrote in a 2016 essay:

“My suggestion is, then, that a major motivation or affluent Scandinavian peasants to engage in long-distance exchange – and thus to enter into a silver economy – was that products acquired in this way could ease some of the most controversial issues of their social networks: the negotiations over the longterm status and personal property with which spouses, women in particular, entered into marriage. The incentive for trade and raids alike, I suggest, was ultimately driven by the hubs of family relations: by marriage and the negotiations or the families connected with it.”

If silver was a fundamental linchpin in the proper functioning of cultural practices that held together nuclear families, silver’s value was paramount to the fabric of society. Value, as economists insist, depends on supply and demand. Therefore, the amount of silver in circulation and its demand had dire consequences for the stability of Viking Age Scandinavian society. Where the supply and demand for silver had remained more or less constant in the two centuries leading up to the Viking Age, an increase in trade in the East threatened to unravel the delicate balance of pre-Viking Age Scandinavia.

Like the economic woes of the 16th century that resulted from the inflationary effect of Spain’s imports of gold from the New World, the influx of Islamic silver may have caused a significant devaluation of silver in Scandinavia. That effect would have had far-reaching consequences even in the most rural settlements. Given the role of silver in early Viking Age Scandinavian society, a sudden shift in the value of silver across Scandinavia may have threatened the most fundamental ties of the nuclear family. In simpler terms, the bride price got too expensive (like housing today).

Of course, there is an assumption here that the silver economy held a kind of primacy in the factors that created the conditions for the Viking Age to begin, which is still widely debated. It is important to understand–and I will continue to stress–that all of the factors discussed herein are part of a much larger tapestry of themes and events, none of which constitute any kind of trigger.

Following the Salt Trail

In the grip of rampant inflation, the amount of silver needed to afford the bride price may have grown out of reach for most men and their families–at least until the silver economy stabilized. Either these men had to find more silver or something of value to take its place—something valuable to the Rus, who, for obvious reasons, would not have wanted to trade silver for silver. Sindbæk further noted in his essay:

“The desires and ambitions, which led to the Viking expansion, were developed through generations of travel to distant markets, in search of things that would reset social balances and make social bonds more durable.”

When the first Viking raid occurred in England in 793 A.D., they had as their target a monastery. Monasteries were remote and ill-defended, and they owned precious metals such as silver. Historians have classically assumed the Vikings struck monasteries for their silver, which aligns with the silver hypothesis proposed by Sindbæk. Except, the closer we examine the early progression of Viking raids, the less sense it makes that silver was their intended bounty.

That first crew who raided Lindisfarne undoubtedly stole away with plenty of silver and portable goods, including enslaved people (as described by Alcuin and Simeon of Durham). Nevertheless, they never returned to that site, presumably because they understood the monastery would not likely replenish their silver for fear of a repeated raid. Alternatively, perhaps the Vikings did not acquire what they had hoped. Anglo-Saxon England was not silver-rich like the Byzantines and Islamic worlds, so the amount of silver they stole in the first raid may not have made economic sense. There is no way to prove it except to follow the trail of where they raided next.

Two years later, the monastery on the island of Iona, an island between Ireland and the island of Britain, succumbed to a Viking raid. Iona stands in contrast to Lindisfarne insofar as the Vikings did raid it again, but decades later. Again we have a case of a raid that did not lead to anything more than terrorizing the monastic world. Four years later, the Vikings made a straight shot for Saint Philibert on the island of Noirmoutier, off the coast of France. The progression seems curious. Ireland and, indeed, the whole of the British Isles had copious amounts of ill-defended and remote monasteries to raid. Why would a Viking expedition risk sailing so much further to France to raid the same thing?

Perhaps the Vikings thought a monastery in the Carolingian Empire might have more silver to plunder. If that were the case, we would expect to see that the first raid had remained an isolated incident. The problem is, we know that in that small corner of the Carolingian Empire, the Vikings returned time after time, almost annually, as related to us by the monk Ermentaire. Silver is not a renewable resource, and a monastery plagued by repeat attacks would have learned to keep their silver somewhere else, somewhere safe.

More curious, the chronicles tell us that after the monks abandoned the island in 836 A.D,, the Vikings used it as a wintering base, and from detailed analysis of the salt trade in the Carolingian empire, we know salt production increased after they occupied it. The historian Michael McCormick, who specializes in the Carolingian salt trade, wrote in a 2001 article:

“Salt and bread were basic to life and to Carolingian commerce. The indispensable condiment and preservative is unequally distributed across Europe and has always figured prominently in early exchange systems connecting different ecological zones…Efforts of Carolingian institutions to buy the salt they needed help us to see it traveling by the boatload up the rivers of Frankland, and by the wagonload over its roads. Indeed, the thrifty archbishop of Sens decided to buy inland at Tours one year: rainy weather had driven up the price at Sens of salt from his usual supply source on the Atlantic coast, several hundred kilometers away.”

Hence, silver does not appear to be the focus of Viking raids and invasions in that part of the world (though they acquired plenty along the way). Their interest in the island of Noirmoutier persisted after the monks abandoned it, and the local production of salt continued to increase under their occupation. Given this evidence, salt looks to be the top candidate for what attracted the Vikings to southwestern France.

Establishing Demand for Salt

The Salt Hypothesis has had a major hurdle in demonstrating a demand for salt in Viking Age Scandinavia important enough to have made salt a primary motive for the Vikings’ westward expansion around the north of the British Isles, through the Irish Sea, and to Southern Brittany in France. As previously discussed, the inflationary effect of the influx of silver from the East required seeking out portable wealth to re-stabilize the economy and, more importantly, close social family bonds. Historians have traditionally cited monastic silver as the Vikings’ primary target and enslaved people as a secondary resource.

The problem with the idea that the Vikings sailed across the sea to loot for silver and enslaved people is that they could have done so with far less risk and much closer to home. We know they raided the Obrodites, the Frisians, and Slavs to the east as early as the 780s. Something else must have driven them further West, something they could not produce readily at home or acquire from their direct neighbors; something they needed more than enslaved people or silver—not for wealth, but for survival.

Since the dawn of civilization, salt has been a crucial resource. It is not a stretch to say there was likely a demand for salt in Scandinavia at the outset of the Viking Age. The question is whether a demand was strong enough to have inspired the first major raids in the British Isles and Western France. For that to have been the case, we would need to demonstrate a critical, life-sustaining need for salt far greater than the mere demands of day-to-day life.

Food preservation presents an enticing prospect for demonstrating a need for salt strong enough to spur the early Viking raids forward. Except, the primary fish they caught, so scholarship has insisted to date, was cod, which the Vikings dried. Hence, a greater commercial demand for salt to preserve their primary food staple hits a stumbling block. If the Vikings dried their fish, they did not need salt in the same quantities as they would need it in the later medieval period, which they used to preserve herring.

If Viking Age Scandinavians did not need commercial quantities of salt to preserve their food, what other activity might have driven its demand? Looking to the East, the Viking expansion up the freshwater river systems of Eastern Europe to Constantinople may offer us the justification we need. An obscure mention in the Saga of St. Olav gives us a clue that may help to demonstrate a high demand for salt. In the saga, St. Olav died in the land of the Rus and was preserved in a barrel of salt until his retainers could transport his body back to Scandinavia. The mention of a barrel of salt stands out.

The Vikings moving East, therefore, carried with them salt, ostensibly to preserve perishables while they navigated up the freshwater Volga and Dnieper rivers. Suppose the Rus moving East needed significant quantities of salt for their travels. In that case, their demand might have exceeded the production capabilities of Scandinavia at the time, requiring imports to meet their needs. The Carolingians, however, controlled all the major salt mines in continental Europe—most importantly, Salzburg—and they restricted trade with Scandinavia starting in the 780s. We know from the sword trade that a black market moved goods across borders between the Carolingians and the Danes, but a black market salt trade may not have satisfied the demands of the Rus.

To this point, the Salt Hypothesis hits the ceiling. This is where it has lived since historians first started exploring the idea more than a century ago. It is where I have parked it since I started researching the topic over a decade ago. In speaking with other historians, I was advised to move on. And move on, I did. Until…

Cutting Down the Tree with a Herring

A recent study out of Norway has given the Salt Hypothesis new life. In fact, it may have given the Salt Hypothesis the teeth it needs to stick in academia. The study concluded that the herring trade started around 800 A.D. rather than 1200 A.D., as previously thought. The implications of the study are dramatic. As previously discussed, the major hurdle the Salt Hypothesis had to clear was establishing clear commercial demand on a level that necessitated a westward expansion to satisfy it. Moreover, the study looked at sites on the Baltic that would have belonged to the Rus and concluded that they traded significant quantities of herring in the east.

The sites the study surveyed dot along the eastward expansion of the Rus, denoting a high demand for the fish in Rus territories. Analysis of the herring bones strongly indicated the herring was caught in Norway and Denmark and made its way east by trade. It could be that the herring trade began as the commodity the Danes and Norwegians needed to balance out the influx of silver from the East. Except, they needed salt to make it work. Herring is a fattier fish than cod, meaning it cannot be preserved by drying but by salting. If the herring trade began at the outset of the Viking Age, the demand for salt it would have created would have far exceeded Scandinavia’s salt production capabilities at a time when the Carolingians restricted trade.

“The herring industry of the Baltic Sea supported one of the most important trades in medieval Europe,” Barrett says. “By combining the genetic study of archaeological and modern samples of herring bone, one can discover the earliest known evidence for the growth of long-range trade in herring, from comparatively saline waters of the western Baltic to the Viking Age trading site of Truso in north-east Poland.”

It was a perfect storm. Islamic silver brought in by the Rus deflated the value of silver. Other groups, such as the Norwegians and Danes, had to exploit a new type of fish to offset the economic imbalance from the influx of silver. That new fish needed salt to preserve it. Scandinavia’s neighbor, the Carolingians, cut off trade to their salt mines. The next natural step is for the Vikings to go looking for salt.

It is unsurprising, given this context, that when the Vikings burst onto the scene in the West, they quickly and intentionally narrowed in on the salt-producing regions of western France and made a business of returning there year after year to exploit a resource they needed to keep their society together.

Returning to Sindbæk’s silver economy hypothesis, the phenomenon of seeking out salt would only have lasted as long as it took to stabilize the silver economy at home. Therefore, we should expect to see the interest in salt wane by the mid-800s and wane it did. The character of Viking activity in Western France–and indeed the Western world–took a dramatic turn in the middle of the century, shifting from sporadic, isolated raids to full-blown invasion attempts. A fresh set of economic, political, and social conditions motivated later expeditions and are not part of this article’s synthesis. The focus here is on the first thirty years of Viking activity in Western France and the British Isles.

The Monastic Trade Network

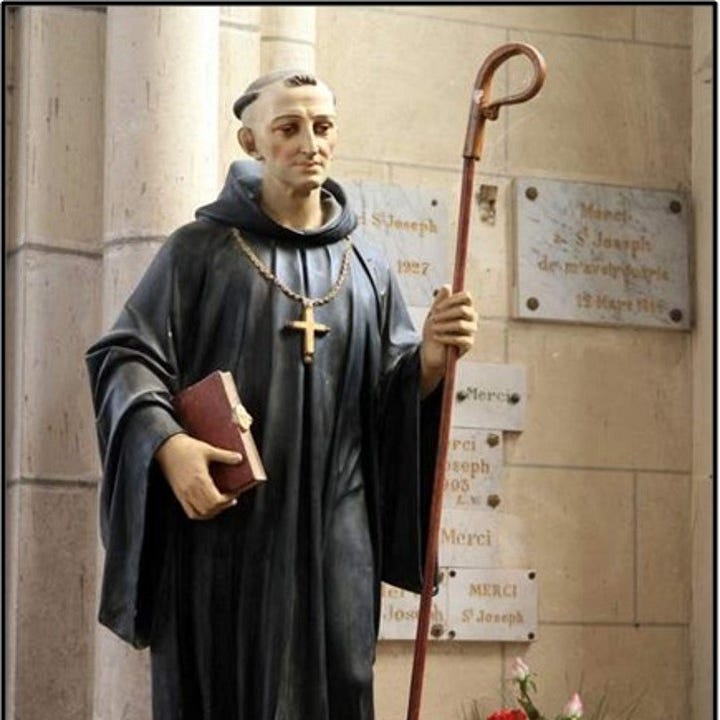

As previously discussed, the island of Noirmoutier has produced high-quality salt from water evaporation pools since Roman times. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Europe experienced several critical transitions. Among them, one of the most critical was the conversion of the Merovingians — a dynasty of Frankish warlords who conquered much of Gaul by the end of the 6th century — to Christianity. Their charismatic leader, Clovis, recognized the advantages of allying with the church and obligated his subjects to join him. The scene of his baptism stands as one of the most celebrated moments in French history. With Clovis on their side, the church expanded quickly across Western Europe and established abbeys and monasteries in every conceivable place the Merovingians would allow. Many of the monks who later earned sainthood lived during this period, including the namesake of the monastery and church at Noirmoutier-en-l’Île: Saint Philibert.

Saint Philibert grew up in the town of Vic in Southern France. His father was a well-respected magistrate and adviser to King Dagobert I. As was common then, his father convinced the king to find a place for his son at the royal court. Little information exists to describe Philibert’s time among the Merovingian nobility, but according to his biographer Ermentaire, he felt dissatisfied with his time among them and chose instead to dedicate his life to God and join the church as a monk. Perhaps he did feel the need to answer a higher calling, or perhaps he fell out of grace with others in the king’s entourage, a fact his biographer might have omitted on purpose. Whatever his reasons, Philibert received approval for his decision from Dagobert and sold all of his material possessions. For the next decade, he worked in various monasteries and, as far as we know, stayed out of trouble.

Around 650 A.D., Philibert had earned enough respect and clout within the religious community to set out on a long journey to study the teachings of other notable monks, including (as they are called today) Saint Basil, Saint Macaire, Saint Benoit, and most importantly, the Irish monk Saint Columban. Philibert had, of course, as his intent to establish his own monastery and holy order of monks based on the accumulated wealth of their teachings, inspired by, and intent to embody the principles of Irish monasticism. By 654 A.D., he received a royal charter establishing his first abbey at Jumièges. As the first abbot of Jumièges, he imposed a particularly severe doctrine of austerity known as the Columban Tradition. During his tenure, he fell out of grace with the Maire of the Palace of Neustria, Ebroïn, and had to flee for his life. Luckily, the bishop of Poitiers, Ansoald, who had admired Philibert’s work at Jumièges, offered him refuge in return for evangelizing his diocese in the St. Columban tradition. Philibert evidently did fine work, and Ansoald rewarded him with land grants at Déas, in Herbauges, and on the island of Noirmoutier, then called Herio. On the island of Noirmoutier, Philibert founded the monastery that would take his name, and he died there on August 20, 684 A.D.

The religious order that took root after his death did not find its footing for several decades. During Charlemagne’s reign, it experienced at least two reorganizations ordered by the church and the Carolingians. It also never achieved full autonomy from the mainland nor developed into a leading intellectual center in the Irish monastic tradition as its founder had hoped. Various bishops, abbots, and other local lords sought to influence the monastery, some going as far as to live there semi-permanently to assert control. If the order had failed to gain dogmatic traction and ritualistic stability, why did it attract so many powerful figures? As is the case today, the main interest lies in the resource it controlled. By the late 8th century, Herio had grown into a major exporter of salt, a resource in high demand in the early medieval period. It is no surprise, therefore, that the lords of the surrounding region and religious leaders across the Christian world sought to capitalize on the island’s potential for wealth. Ansoald, it appears, did not fully appreciate the value of the land he had given to Philibert—or perhaps he did.

Philibert’s biography, Ermentaire’s Miracula (miracles), tells us of the widespread appeal of the island’s salt. Numerous mentions of ships from Brittany, Nantes, and, more importantly, Ireland indicate a thriving trade network that spanned the Western sea routes. A church document from the seventh century tells of a ship loaded with Noirmoutier salt destined for a monastery in Ireland. Given the heavy influence of the Saint Columban tradition, the monks of Saint Philibert kept in contact with other monasteries in the British Isles founded on the principles of Irish monasticism. Those contacts would have included liturgical exchanges as well as moveable goods.

If salt from Noirmoutier had made its way to Lindisfarne, how would it have gotten there? It would have followed the monastic trade network from the island of Noirmoutier to Ireland, Iona, then over the top of the British Isles to Lindisfarne. If we follow that same trajectory in reverse, it mirrors the trajectory of the first Viking raids.

Telling the Story of the Salt Hypothesis

Norway, 793 A.D.

A small fishing village on the western coast receives a visitor. It is a trade ship from Gotland looking for salted herring to trade to the Rus. The village has herring but laments to the traders that they do not have the salt to preserve it. The merchant who supplied them with salt never showed (the Carolingians cut off trade with the Danes, putting him out of business). Soon, the Swedish ship moves on, disappointed. The village chieftain, Oskar, is disappointed, too, because he needed the silver from the trade to afford the bride price for the neighboring chieftain’s daughter to marry off his son.

Since the Rus started bringing back hordes of silver from the east, the bride price tripled. Oskar does not understand how or why that is, but he does know they use that silver to buy herring. If he cannot afford the bride price by the next time a Gotland ship arrives to trade, the neighboring chieftain may marry off his daughter to a rival, bringing him a risk of war. The chieftain, desperate to secure the social bonds to preserve peace, organizes an expedition to acquire wealth abroad.

Arrived in Lindisfarne, the chieftain finds a barrel of salt with large crystals indicative of an evaporation pool technique unavailable in Scandinavia. He questions the monks and takes some as slaves. Over time, one of those slaves learns the language, and the chieftain keeps him as an advisor. While the wealth from Lindisfarne more than afforded the bride price, the chieftain sees an opportunity. He organizes another expedition, this time with the guidance of his enslaved monk, who takes them along the monastic trade route, and raids Iona. Again, they find salt, leading the chieftain to ask where to find its source. The chieftain knows that if he can secure a steady import of salt to prepare his herring, he would make his people rich trading with the East. In 799, he finds Saint Philibert and its salt. From there, he starts the century of Vikings in Brittany, establishing a shipping lane back to Norway to supply the herring fisheries and, by extension, the eastward expansion of the Rus.

Concluding Remarks

The idea that salt was the primary target for the Vikings in France is enticing. It helps to explain some of the enduring mysteries of Viking activity in southwestern France and Brittany, such as the frequency and persistence of the early raids.

Still, more work must be done to prove the connection between the Vikings’ early westward expansion and salt. Chief among those: more work needs to be done to show the movement of salt within the monastic trade network, which we don’t have.

Furthermore, while the herring bones found in the Baltic have proven interesting, they would need to have been found with salt demonstrably from southwestern France for the Salt Hypothesis narrative to stick. Perhaps one day, the same team who discovered the herring trade started in 800 will look for signs of the salt used to preserve it.

There are other holes in this story, as I am sure several of you will be more than happy to point out in the comments section. But, the recent study on herring has helped reinvigorate my research and push forward this idea I have wanted to prove or disprove for so long.

Quote sources:

Bergier, Jean-François, Une Histoire du Sel. Fribourg, Switzerland: Office du Livre, 1982: 116.

Sindbæk, S. M. Urbanism and exchange in the North Atlantic/Baltic, 600–1000 CE. The Routledge Handbook of Archaeology and Globalization. T. Hodos, A. Geurds, P. Lane et al. Abingdon, Routledge, 2016.

McCormick, M., F. G. P. M. H. M. McCormick and C. U. Press. Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce AD 300-900. Cambridge University Press, 2001: 698.

Atmore, L. M., Makowiecki, D., André, C., Lõugas, L., Barrett, J. H., & Star, B. “Population dynamics of Baltic herring since the Viking Age revealed by ancient DNA and genomics.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119 (45), 2022.